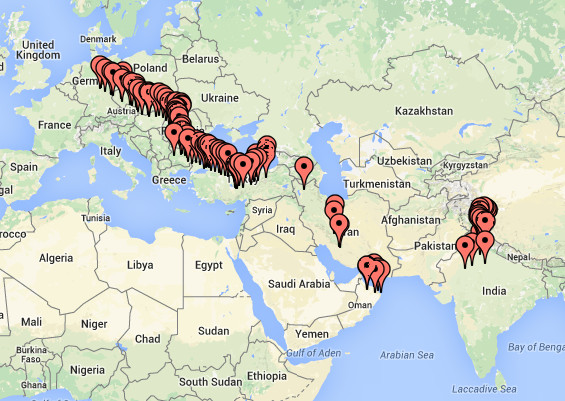

Journey to the East 2013

Marco Polos fabulous journey to the East left wild dreams in my mind since I was reading it as a child. Herrmann Hesses "Journey to the East" did so some years later, as well a a picture book about the Himalayan - the roof of the world. And finally after a long winter the snow melts. Now Kathrin and I are ready to venture out to a long bike journey - to hopefully meet a lot of friendly people and face incredible landscapes and colorful cities from here to the Himalayan.

- Details

- Category: Journey to the East 2013

Buddhist prayer wheels on the roadside and colorful prayer flags above the old houses are a common picture in Rampur as we cycle to the bus terminal. As Nina and Daniel told us the night before, the NH22 to Spiti Valley gets very bumpy and dusty not long after Rampur. An incredible one-lane road has been milled into the cliffs of the narrow Satluj gorge. In the event of opposing traffic, very precise and skillful driving is needed to avoid disasters. Vishnu Ram, a police officer from Puh sits beside us and advices us to get the so-called Inner-Line permit for Spiti in Rekong Peo rather than in Puh (as stated before in Shimla).

People of Kinnaur (that's the name of the district) wear brimless gray hats with green patch, and many of them look fairly Chinese. The Tibetean border is just a mountain range away. We reach Rekong Peo late in the afternoon, by the time we expected to be in Puh already. And we would only get our permits on the following day a man at the tourist information tells us. Well then, we have beers and enjoy the view of the full moon illuminating the snow-capped peaks of Kinner Kailash on the other side of the Satluj valley.

After a thin coffee we get our permits and find a bus for Puh by lunchtime. Landslides and shooting stones are a major problem on this narrow road stretch underneath giant debris mountain slopes. We spend almost two hours waiting on the road for a time slot without shooting stones. A hiker from Chandigarh states: “The world is crumbling” while another series of football-seized rocks crashes on the road in the bend before us. Eventually the bus moves on. Yet the ride is not for the faint-hearted, the narrow bends of the road are framed by rock walls and abysses. Every now and then a crew of women maintains the road. They carry large bowls of concrete on their heads and little children on their backs. Smiling, crashing rocks with hammers. By nightfall we reach the diversion to Puh, unload and pack our bicycles and pedal 4 kilometers of switchbacks up to the actual village.

Vishnu Ram, the police man finds us when we are about to leave the next morning. He invites us for a tea and gives us detailed information about the road to Nako. We jolt on to the mouth of Spiti and Satluj, then tackle the first series of switchbacks high above the Spiti river. There is no traffic anymore, and not much settlements. In a small village, we are happy to find a very basic Open-Air Dhaba (primitive roadside restaurant) and scoop truck driver portions of rice and Dal. The very truck drivers would often stop and hand us some of the incredibly sweet apples from the region. More and more switchbacks are to come, and by nightfall we finally arrive in Nako. The GPS states 3700m above sea level, our tourist map indicated just 3000m. A small typo can make a big difference for a cyclist...

Terrace fields and orchards surround the peaceful Nako village with its picturesque clay houses high above the river. Peas grow here, vegetables and barley as we learn later. Cows and goats occupy the narrow lanes between the stone walls, and prayer flags just perfect this ensemble. With two monks from the Buddhist monastery we hike up a neighboring hill with a splendid view over the Spiti valley and the snow-covered Mount Shipki. Tibet is incredibly close. Horse trails lead there, and the locals may exchange cows and stuff with their neighbors. The Spiti people use the Tibetan script, but have their own language, Botu. The food is also more influenced by Tibet than by India. Momos (tasty dumplings filled with vegetables, or cheese or potato) are widely available, and different types of thick noodle soups and Chowmei. Actually, noddle soups are our favorite for the cold evenings up here, and Chapati are hard to come by. Instead, they have Tibetean bread sometimes. That is thick fluffy flatbread and even better than Chapatis.

With a truck blocking the road to Tabo, we enjoy a cycling day with no traffic. After 20 kilometers downhill to Chango at the river side, there is another 30 kilometers of bumpy up and down between giant debris slopes and narrow gorges. Colorful rock formations spoil the eye in absence of vivid green. The incredibly turquoise Spiti river has carved a truly fascinating landscape between the mighty mountains. We reach Tabo with dusty aching bicycles, and bump at the bus stand into Carola and Felix, a German couple. They have spent two weeks teaching English and collecting cow dung in a monastery near Kaza, and tell us a lot about their journey as street musicians and artists. Together we check in to the monastery's guest house and spend the time waiting for our ascetic (but delicious) meals in the attached restaurant.

On the next morning, Tabo feels as numb and sleepy and dry as my ears and brain and throat, respectively. Damn, I got a cold. But hey, I wished for peace so desperately just a few days ago! The tourist season is long over, most guest houses and restaurants are closed. Wandering the empty streets in the cold leaves a strange sensation in me. I need to get out of our dark room, and so Kathrin and I check into a different hotel. Carola and Felix join us there for a jamming session with three other backpackers in the late afternoon sun. Passing by neighbors listen to the sound of violin, accordion and guitar. “On the road again” we sing and my spirits rise.

I manage to attend the morning prayer in the monastery. Monks mumbling mantras. Me with a dripping nose, far away from enlightenment. Tabo is famous for the paintings in the 1000 year old Buddhist temples. From the outside, they seem just like a number of clay houses. My head still feels like a cotton ball when we enter the temple area. Ali, a young German who has been traveling in the Himalaya for half a year is sharing his knowledge of the various painting techniques of the ancient frescoes. In the evening we find a proper Dhaba that serves food in less than 10 minutes, at quantities cyclists need. I feel much better after.

A dusty day ride away from Tabo is the town of Kaza. Of course it is cold here too, but with the shops and tea stalls open, it feels way more lively and charming. We stay two nights in a traditionally built clay house, and visit the nearby Kee monastery. The white painted monastery houses on the rocky ridge look almost like a snow cap at 4000m above sea level. Young monks try to ride Kathrins Freddy yet the dark red monk clothes are anything but suitable for the task. The view from the monastery over the suddenly wide Spiti valley with naked brown terrace fields in front of the mighty mountain ranges is splendid.

We have Yak-Tanduk, the thick home-made noodle soup for dinner with our hosts. It is our first meat meal since we are in India, and it tastes incredibly good. With the help of the family, the owner of the mobile phone Kathrin found on the roadside the day before can be traced and contacted. Tick that. Time to move on before we get snowed in.

Our plan to reach Lhosar appears pretty ambitious in the fierce headwind early afternoon. Lots of ups and downs and the pothole spiked gravel road leave no chance to maintain a pedaling rhythm. No Dhaba for 50 kilometers. The sweet chickpea balls we carried as emergency food don't warm me up anymore. The constantly running nose and the outlook of at least three more days on even worse roads lets my cycling enthusiasm crumble. Another set of bumpy switchbacks ahead. Shivering to the bones we arrive in Hansa, 8 or 9 kilometers before Lhosar. No guest house to see, the Dhabas are closed.

We ask some locals. One of them, Navang, invites us for tea to his house. He is a local healer, and right away senses our misery. In the dark kitchen of the clay house, there is a small stove we sit around, and sip about a liter of hot Chai to warm up. Navang proposes that we could stay here for the night, have dinner at a nearby wedding and get a lift to Manali on the following morning. Sounds like a new plan!

{youtube}QnyeT4VZy-o{/youtube}

After dinner we are guided to a long and narrow room full of young men sitting on rugs. There is a 10 liter bucket of self-made Spiti beer (that has little to do with the beer we know) plus some bottles of self-made barley whiskey, and the lads have been sitting already a few hours. We talk, drink and sing and pass time. Weddings used to last for five intense sleepless days. Nowadays it is compressed to two, which perhaps serves the health of the attendees. After some photo shooting, Kathrin and I receive white Tibetan “Good luck” scarfs.

Tsering, Navangs father appears early in the morning to lit the cow-dung stove in our room. We talk about the Tibetan healing with the three-finger diagnosis, about the Botu language being the key for learning it. Apparently, winter is the best time to study here, for there is nothing else to do. A German, Peter van Ham, who has been here often, wrote a book about the valley and its traditions. Then our jeep arrives. Or rather three of them. Our luggage and bicycles are spread on the roof carriers, and we are fitted neatly with 8 other passengers in one of the Jeeps.

The road winds up from Lhosar towards Kunzum La at 4500m, where we stop for some prayers. Incredibly beautiful snow covered mountain ranges surround the white Stupa, covered with scarves and prayer flags. With no more than 20km/h we move over the bumpy track and through icy creek crossings through the Lahaul Valley. For me it looks like an endless stone desert, framed by mighty mountains. Nothing seems to grow here, no one seems to live here. Those expensive modern City Jeeps would probably not last long on these roads, but the Indian Mahindra Jeeps master the track.

Only a single Dhaba is open on the 80km stretch between Kunzum La and Rotang Pass since the tourist season is over. It would have been mission impossible on the bikes with our three packs of instant noodles. The fantastic view of a paved road winding all the way down from the Rotang Pass through green forests towards Manali makes a cyclists heart jump. Colorful paragliders hover in the mystic afternoon sun. Unfortunately, my bike is on a Jeep that has long reached Manali, but a seed was planted at that moment.